“Irrational” Tenants Scupper Government Transfer Policy

Posted: January 29, 2004 Filed under: Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on “Irrational” Tenants Scupper Government Transfer PolicyFollowing the recent rejection of ALMO (Arms Length Management Organisation) in Camden and a series of setbacks in other parts of the country, the government’s attempts to sell off council housing appear to have hit the buffers. The government hopes to rid itself of the burden of council housing by only releasing funds for ALMO, stock transfer and Private Finance Initiatives – if only it weren’t for those pesky tenants! Responding to the recent reversals, housing minister Keith Hill labelled tenants who have voted against transfers and ALMO as “irrational”. Surely the single most irrational element in this is the government’s dogmatic insistence that money should only be made available if tenants vote to end council housing. If the money’s there for schemes such as ALMO, what’s stopping them spending it on improving the quality of council housing and keeping it within council control?

We’re not under any illusions that council housing is in a healthy state – far from it. But at least with the council you have the ultimate say. If you don’t like the way they deal with it you vote them out! There’s no such say with Housing Associations and ALMOs. And with proposals for Haggerston West and Kingsland Estates in Hackney apparently only offering stock transfer options (with a smattering of private housing to appease the city workers spreading down Kingsland Road), it’s an issue that has local as well as national importance.

In a recent Guardian article “Minister refuses to back down over unpopular transfer policy”, the full scale of the government’s housing problem is revealed:

The housing minister has blamed tenants who vote against ditching their council landlords for the government’s likely failure to meet its manifesto commitment on decent homes.

Appearing before a parliamentary inquiry, Keith Hill insisted that the government’s policy of hiving off council homes would not be scrapped in the face of tenant opposition to the idea. He also said he was “tearing up” former local government secretary Stephen Byers’ commitment to give all tenants the right to a decent home even if they opt to keep their council landlords.

Asked whether the government would meet its target of repairing all council homes to a decent standard by 2010, Mr Hill refused to give a straight answer. Appearing before the select committee for the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister he said: “We are determined to work with local authorities to ensure the target is reached, but it takes two to tango.”

He added: “If local authorities don’t measure up to the opportunities then there’s a limit to what the government can do. There’s an additional issue if tenants themselves vote against the opportunity.” Mr Hill also conceded that the interim target of repairing a third of homes by March 2004 will not be met by the deadline, but some time “in the course of the year”.

The government insists that the extra money for meeting the target will only be available to councils that hive off their homes in one of three ways: transferring them to housing associations; switching housing management to so-called arm’s length management organisations (almos); or repairing them through a private finance initiative consortium.

That policy was thrown into doubt earlier this month by an overwhelming vote in Camden against setting up an almo. Camden has now exhausted all three of the government’s options but it still needs an extra £283m to meet the decent homes target.

Mr Hill insisted that the government’s three-option policy “had not changed in light of recent events in Camden”. He added: “There will be no so called fourth way. The cavalry will not be coming over the hill with alternatives.” But he conceded that this may mean the government misses its manifesto pledge. “You can bring a horse to water, but your can’t make it drink. We don’t want to force tenants to accept changes they don’t want.”

Mr Hill said the Camden vote was a “singular event”. He blamed an “unscrupulous” campaign by Defend Council Housing, which he dismissed as a “combination of superannuated Communists and not much younger Trotskyists”. He suggested that Camden should work with the 70% of tenants who did not vote in the ballot.

He also admitted that a vote in 2002 against transfer in Birmingham was a “setback” to the government’s policy. Birmingham requires an extra £1bn to meet the 2010 target, but it has little prospect of raising that money through the government’s three options. Mr Hill added: “I’m extremely conscious of the Birmingham experience, we are heavily engaged as a department with Birmingham in seeking a way forward.”

Mr Hill also sought to avoid the embarrassment of missing the decent homes target by watering down the wording of the commitment. Speaking after the hearing he said: “We want to ensure that every tenant who needs his or home improved has the opportunity to do that. If they chose not to that’s a matter for them.”

When it was pointed out to him that giving tenants the opportunity to improve homes was different from the manifesto commitment, Mr Hill said the government had to assume that tenants would vote “rationally”.

Strong Arm Tactics over Arms Length Management

Posted: November 21, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Strong Arm Tactics over Arms Length ManagementWith Hackney Council’s Jamie Carswell already a firm believer, ALMO is a distinct possibility for Hackney’s council housing stock. As highlighted by the IWCA in a recent letter to the Hackney Gazette, ALMO is another means of privatisation. But recent developments in neighbouring Islington and nearby Camden, should be an eye-opener for those people who think Hackney council will listen to tenants’ views when the decision is made. Reprinted below is an article from Islington IWCA’s website outlining major concerns over how the council is handling the issue. This is followed by a story from Inside Housing website on Camden’s rush towards ALMO.

Ballot on Almo is agreed – but can it be fair?

(Highbury & Islington Express – Article – 14.11.03)

Angry campaigners say the vote on the future of their homes is being steamrollered by council propaganda.

Until last week Islington Council had steadfastly refused a ballot on proposals to set up an Arms Length Management Association (Almo) to take over running their housing estates.

But the Islington Independent Working Class Association (IWCA) says the last minute decision to ask tenants if they favour an Almo was a deliberate attempt to stifle debate prior to the vote.

Gary O’Shea, of the IWCA, said: “Most tenants received their ballot papers just two days after the announcement was made. The council is obviously trying to push this through quickly.

“I think it had started to panic that plans were beginning to unravel. Early last week a tenant representative on the Almo Shadow Board was frogmarched from the building because he refused to sign a confidentiality agreement preventing him from telling tenants the real facts.

“Councillors have refused to turn up to any meetings organised by tenants who were not hand-picked by them. And the ballot papers have been sent out in the same envelope as pro-Almo propaganda leaflets that have “vote yes” in them 21 times. The council has mounted a propaganda offensive so one-sided it would put any tinpot dictatorship to shame.”

There is also concern about the way the decision to hold a ballot was taken. Labour leader Mary Creagh said: “Councillor Hitchins leaked the news of the ballot on Tuesday when the decision was supposed to have been made openly and democratically at Thursday’s executive meeting.”

But Cllr Hitchins said it had always been his intention to hold a ballot and that it was necessary to get on with it to stop the spread of inaccurate information.

“Once people know there will be a ballot they want to see it quickly,” he said. “Camden had a six month gap between the announcement and the ballot and I couldn’t believe the amount of misleading and untrue facts people were told in that time.

“I told the press the executive was likely to agree a ballot on Thursday because the truth is we’re not going to vote against our colleagues on decisions as big as this.”

Tenants and leaseholders can vote on the proposal by phone on 0800 081 0202, on the internet at www.election.com/islingtonalmo or by post. The ballot closes at noon next Friday.

‘Totalitarian’ ALMO campaign under fire – Inside Housing website

The row over Camden Council’s bid to set up an arm’s-length management organisation has escalated with campaigners threatening to lodge a judicial review accusing the council of circulating misleading information and proposing a biased ballot question.

With the ballot due to start next week, lawyers acting on behalf of two tenant campaigners have written to council chief executive Moira Gibb alleging that most of the information circulated is ‘entirely one-sided’.

They also say the proposed ballot question will ‘lead many voters to conclude that a no vote is tantamount to voting against improvements in their dwellings’.

Campaign group Defend Council Housing has said the council could be acting unlawfully and has demanded it changes the ballot question and distributes a leaflet setting out some of the arguments against the ALMO.

But the council has rejected the allegations and roundly refused to change the ballot question. A spokesperson said: ‘The overview and scrutiny commission considered the matter and felt the proposed ballot wording to be neutral, factual and fair.’

Campaigners have also levelled charges of ‘totalitarianism’ at the council after it emerged that that senior managers at the authority ordered the removal of anti-ALMO posters from council properties by lunchtime tomorrow.

Unison assistant branch secretary Anton Moctonian said: ‘We are asking our members not to carry out this task until we have sought advice on this. These tactics have more in common with those practiced in totalitarian regimes as opposed to democratic and free societies.’

DCH national committee member Alan Walter added that his organisation would fight back by replacing any poster taken down by the council with ‘at least 10 additional posters’.

A spokesperson for the council said that posters would only be removed if they were an eyesore.

She said: ‘Patch managers have only been told to remove them from areas where they are not creating a welcoming atmosphere’.

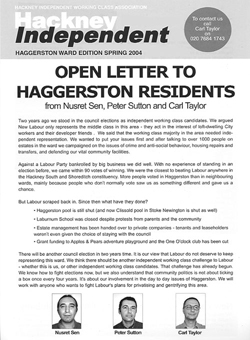

Haggerston Tenants Reject Imposition of Private Company

Posted: November 7, 2003 Filed under: Gentrification / Regeneration, Haggerston, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Haggerston Tenants Reject Imposition of Private CompanyOn 1 November 2003, Pinnacle took over the housing management of St Mary’s Estate in Haggertson. Despite calls for a tenant ballot on the issue, the council undertook a limited consultation exercise, the results of which have not been made public. However, at a meeting in early August, 30 out of 35 people asked for a choice to remain with the council.

Ignoring the results of this consultation meeting, the council’s cabinet decided to press ahead with the transfer of estate management to Pinnacle. It should be noted that the choice tenants were given by the council was between privatisation this year, or possible privatisation next year, ie no real choice at all.

Hackney Independent Working Class Association has spoken to nearly half the tenants on St Mary’s, 160 of whom have signed a petition calling for a tenant ballot on the issue and to be given the choice of remaining with the council. The petition has been sent to Cllr Jamie Carswell, head of Housing at Hackney Council.

As a tenant from St Mary’s states, “The majority of tenants and residents were unhappy that there were only two options on the voting paper and most added a third option stating that they wanted things to remain as they were. These feelings were ignored as was a direct question to Jamie Carswell asking for a ballot”.

IWCA spokesperson Carl Taylor said : “This is not about the rights and wrongs of privatisation – although the IWCA is opposed to it – but the fact that tenants have not been given a real choice or the opportunity to vote on the matter. Consultation New Labour-style is clearly no substitute for genuine democracy.”

Privatisation, Privatisation or Privatisation?

Posted: September 18, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Privatisation, Privatisation or Privatisation?An article in the Hackney Gazette (4th September) saw the Labour council’s cabinet member for housing in Hackney, claim that tenants will have a choice on the option we prefer for matching the Decent Homes Standard. In response to this article, Hackney IWCA had the lead letter in this week’s Gazette. The Council’s obvious liking for ALMO (Arm’s Length Management Organisations) is something that we have observed for a while now and it is something we will continue to monitor. Islington IWCA are actively opposing ALMO in their borough and here we link to their website’s coverage of the campaign. Below we reprint the full version of our letter in response to Jamie Carswell’s comments.

Jamie Carswell (‘£450 million’ – Hackney Gazette – 4.9.03) tells us that we have three options available if we are to meet the Decent Homes standard in Hackney – stock transfer, Private Finance Initiative or ALMO. Because the council already knows how unpopular stock transfer and PFI are with most tenants, our cabinet member for housing paints ALMO in glowing terms but at the same time claims the choice between the three “genuinely isn’t decided”. Does anyone else smell a rat?

What we are being presented with is the “choice” between privatisation, privatisation and…privatisation. What choice is that? Can we trust a Labour government who have gone on record as stating that they wish to abolish council housing? And can we trust a Labour council whose record on “consultation” consists of listening to what the community says and then going ahead and doing what they themselves want anyway?

Hackney Labour Party tells us that with ALMO, rights of tenants and council employees will not be affected and it is simply a means of putting in extra money and increasing tenant participation. But if that was the motivation, the Chancellor Gordon Brown could sign the cheques tomorrow and draw-up new laws guaranteeing tenants a bigger say in how their homes are run without setting-up an ALMO.

Once again, Labour offers us a sham consultation in an attempt to sugar the privatisation pill.

Yours

Peter Sutton

Hackney IWCA

For more information on the IWCA’s policies on this issue see www.iwca.info

Responses to Crowded Out

Posted: June 24, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs, Schools Comments Off on Responses to Crowded OutLast week we printed a copy of a Guardian Education article on closing schools in Hackney. Interestingly, in the same week we found out that Laburnum Primary in Haggerston had been taken off special measures but was still to be closed. Below are responses to the article from the head of the Learning Trust and a governor of Stormont House School. Tomlinson spins a nice angle on the story but it’s revealing that a man who argues he wants to” raise the level of public debate” on education in Hackney should so blatantly disregard the concerns of parents, teachers, pupils and support staff at Laburnum and Kingsland by closing down both schools.

Closing Kingsland

I was concerned at a number of aspects of your article (Crowded out, June 17) concerning the closure of Kingsland school in Hackney by the Learning Trust.

I was astonished that nowhere did you state clearly the reason the Learning Trust took action to close Kingsland. In November 1999, Ofsted inspected the school and found it failed to provide a satisfactory standard of education. That has remained the situation throughout the last three and a half years. Consequently pupil numbers plummeted as parents and children declined places at the school. The Learning Trust is not prepared to have parents send their children to such a school.

It is relatively easy to suggest that the school should have been kept open another year until Mossbourne Academy opened. It is harder to identify a reasonable message we could have sent to parents whose children were to start at the school in its last year. “Please send your children to this failing school that we intend to close” is hardly a responsible position for the Learning Trust or any local education authority to have taken.

As you rightly note, for existing key stage 4 pupils we indicated we would make an arrangement with local further education colleges. This is exactly what we have done, as you again record. To call this chaos is an odd use of words. I recognise that leading articles linking chaos and Hackney have been common in the past. This, however, is no longer the case.

The Learning Trust has conducted all the business of closing Kingsland school in the proper public arenas. The proposal was quite legitimately challenged, and as a consequence was passed to the schools adjudicator. This independent public body supported the trust’s proposal to close Kingsland and the arrangements for the continuing education of those pupils still in the school.

We want to raise the level of public debate around education in Hackney and in this spirit we welcome criticism, even when for the sake of emphasis it parts company with reality.

Mike Tomlinson

Chair, the Learning Trust, Hackney

Will sense prevail?

As a school governor in Hackney for 17 years, I found your article did not tell the whole story surrounding the closure of Kingsland school.

In autumn 2001, governors of Stormont House school, a highly successful special school in Hackney, were asked by the then LEA to second our headteacher, Angela Murphy, to Kingsland school with the clear objective of turning round what was then a failing school.

However, less than halfway through her time there, the LEA (even before the Learning Trust took over) started consulting on the closure of Kingsland. It is a testament to the leadership shown by Angela Murphy that, notwithstanding closure proposals hanging over the school, Kingsland has now come off special measures within weeks of its closure.

Therefore Kingsland school is only dying because the Learning Trust was determined to kill it.

What is clear is that the lack of democratic accountability of the Learning Trust has allowed the situation to develop, with the council’s education scrutiny panel apparently powerless to intervene.

Must we wait until the Ofsted inspection this September for sense to prevail?

Andrew Bridgwater

Hackney

Crowded out

Posted: June 17, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs, Schools Comments Off on Crowded outReprinted here is a long article from the Guardian’s Education supplement. It covers the recent closure of Kingsland School but also looks at the bigger picture of why Hackney Council is closing schools and the creep towards privatisation being imposed by national government policy with its specialist schools drive and local government with its unwillingness to listen to the concerns of working class residents. Looking at the article, you might ask yourself why a school in Stoke Newington which is obviously successful and serving a generally more middle class catchment area can get £1 million in extra funding whereas a school like Kingsland which is improving from its “failing” status can be axed. Class sizes or class discrimination?

There is chaos in the London borough of Hackney as one school is forced to close and another is forced to take extra pupils. Melanie McFadyean reports

17th June 2003

The Guardian

Almost half of all Hackney’s children go out of the borough to school. Many of them have no choice. Of the borough’s nine secondary schools, one is for boys, three for girls, three are denominational and two are coeducational. One of the co-eds, Kingsland, is about to be closed. The other is Stoke Newington school, which, under its current headteacher Mark Emmerson, is much sought after and over-subscribed.

In April, Emmerson sent out a letter to parents. (I declare an interest here: I am a Stoke Newington parent.) As a result of the closure of Kingsland, itself a matter of pain and controversy for its pupils, parents and teachers, Emmerson was told by the Learning Trust, Hackney’s education authority, that his school would be taking an extra 29 pupils in year 7 in September. (Had the Learning Trust tried to put 30 in they may not have got it past the relevant committees, as 30 constitutes an extra class.)

Given the overcrowding, why was the school expected to take on so many extra pupils? Because, said a Learning Trust spokesman, it was deemed to have the space.

Emmerson didn’t agree. “We will be too overcrowded,” he wrote to parents. “With increased numbers, the first things to break down are the systems we have for managing students; behaviour and attendance are particularly hard to maintain. We do not have enough staff. We do not have enough money, we do not have enough room. It is suggested that we convert offices, dining rooms and the staff room into classroom space.”

In order to maximise space, Emmerson told parents he would need £1,170,000. “We’re having to fight for every penny because there isn’t contingency in the budgets to deal with these issues,” he told the Guardian. “Success is a hard-won prize and very easily damaged, and that’s why I am fighting for the resources. We are dealing with the fall-out from the Kingsland closure and there is no recognition that this has an impact on schools around them.”

By dint of relentless pressure on the Learning Trust and the DfES, Emmerson has secured a substantial tranche of the £1m-plus. A compromise has been struck. But meanwhile what is happening to the Kingsland pupils and their teachers?

“We are not helping Kingsland,” Emmerson explained. “The 29 students will not be from Kingsland families.” So where are the Kingsland children going?

Of those on roll at the beginning of the year, some have already been “shuffled out”, as the Learning Trust’s director of pupil services, PJ Wilkinson, explains. There is a lot of turnover, or “churn” as it is known, in Hackney, so as places became available during the year, kids were moved on. Some Kingsland teachers weren’t happy about the way this was done: according to one teacher there, pupils would simply not turn up and it would transpire they had been moved. Wilkinson says the speed of changeover was surely “a good thing, not a bad thing”.

At the end of May, Wilkinson told the Guardian: “We are seeking school places for approximately 150 students in Kingsland years 7 and 8 in alternative local schools. So far these places have mainly been identified in out-of-borough schools, although there have been small numbers placed at several Hackney secondary schools.”

But 105 in current years 7 and 8 have not yet been placed for September. “I cannot say where they are going. Many have turned down offers, some are holding out for Stoke Newington,” says Wilkinson. “We believe they will be placed but they will be subject to considerable pressure when places come up.

“If they have turned down two places, we’d have to take the position that parents are being unreasonable. They have to take responsibility. We want consent not coercion, but coercion comes at the point at the end of the process. We are trying to steer them without using the maximum harshness that we are allowed to use. It’s terribly difficult.”

There have been problems, too, for current year 9 students. At the beginning of May, a Learning Trust representative told the Guardian that the remaining 141 pupils would go to the Sarah Centre, a new “14+” centre at Hackney Community College, for the two years of their GCSEs, where they will apparently have a pupil-teacher ratio of one to eight. But it would appear this key stratagem was not, in fact, signed up. Jackie Hurst, head of marketing at the college, said: “We are in the middle of considering it.”

On May 20, PJ Wilkinson said the college had given agreement to go ahead, although contracts were still being written. But on May 22, Hurst said: “There is no definite news on the movement of children from Kings land school; we won’t know anything [until] some time after June 2.”

On June 3, a spokeswoman at the college told the Guardian: “Our governors are hoping to take a final decision on whether Kingsland pupils will come to the Sarah Centre on June 10. Nothing has been agreed.” In the event, the deal was rubber-stamped.

Asked what she thought of the trust’s assumption that the centre would sign up, Hurst said she supposed it “was a risk they [the Learning Trust] took. Presumably they had no other option.” The Learning Trust said: “This agreement with the colleges was included in our submissions to the adjudicator on the closure of Kingsland. This has been agreed at progressive levels of detail over the last few months.

“We have a strong partnership with the colleges, who have been happy to speak to students over the last few months on the understanding that they would deliver, as is now the case.”

The impression that the Sarah Centre was definitely signed up was underlined by the Learning Trust’s directions to pupils at Kingsland for choosing their GCSEs.

The pupils going to the new centre were shown their GCSE options at a meeting in school on April 9. A few weeks later, another option sheet was given out. It was a list of seven compulsory subjects, with students asked to select three choices from a grid of subjects. There was no language option, Turkish and French having been deleted from the former list. A note explained that foreign languages will be on offer “where appropriate”. GCSE students will have been relieved to hear last week that there would now be “opportunities to study foreign languages”.

But the choices are tight. A student could not, for example, study geography, history and sociology – only one would be on offer. In the compulsory vocational list, from which students must pick one, are business studies, construction crafts, food technology, health and social care, leisure and tourism and motor vehicle engineering. There may be students to whom none of these appeals. Others might like to do more than one.

“This is a dumbed-down curriculum, and for some of our kids this year 9 to 11 period is the one chance they have – and it’s a chance that’s in danger of being blown,” says one Kingsland teacher.

The teachers were told of the proposal to close the school in July last year, and were offered a special one-off payment as an incentive to stay for the final year, a proposal that was to be clarified at the start of the academic year. The NUT didn’t get copies of the proposals until the end of February. It had asked for an across-the-board payment, but the plan was instead to pay between £3,000 and £6,000, with higher rates going to senior management.

There were strings attached. Anyone suffering more than 10 days sickness during the year would be paid only at the discretion of the Learning Trust. “Failure to accept the above in its entirety,” wrote Wilkinson, “will result in withdrawal of the scheme.”

People felt “deleted”, as one Kingsland teacher put it, and some decided to get out early. “Some of these are people who would have been prepared to work for another year or two to see the kids through. There will be continuity problems for kids going on with their year groups without the teachers they know.”

Redundancy would be an option, although redeployment was not ruled out. In May, Cheryl Newsome, executive director of people management at the Learning Trust, sent letters giving an estimated redundancy/early retirement quotation. But she added that final decisions would be made by the director of education and would be “based on the contingency of the service. If there is a suitable alternative post… the organisation will not authorise redundancy.”

Mark Lushington, spokesman for Hackney Teachers Association, which represents NUT members, says: “Many people have made plans on the basis of being made redundant and do not want to be redeployed.” They may have little choice.

Mark Emmerson says he would like to have seen Kingsland left open for another year until a planned new school, Mossborough Academy, opens in September 2004.

“Kingsland is an improving school, it isn’t going down the pan and if they’d waited, all the issues would have been sorted [and] it might have provided a better educational environment for the students.” Anne Shapiro, head of nearby Haggerston school for girls, agrees. “A lot of us feel the school is making progress. The school could have been given more time to improve and been allowed to see if it was possible to come out of special measures.” (The school is due for an inspection at which this is expected to happen.)

Wilkinson counters that Kingsland was a dying school and it would have been a “betrayal” of Hackney parents to keep it open. “If you move students en bloc you reproduce the same problems. You can’t shake off reputations; it’s better to break the thing up than keep it together.

“Fresh Start didn’t work. The new schools weren’t new enough and the bad reputations were transferred.”

There is a subtext at work in this story. Hackney desperately needs new schools, which it will get only if it conforms to the government’s strategy of setting up city academies. When Emmerson went to the DfES with Wilkinson in May, he recalls, “we suggested some recording of the pitfalls experienced during this school closure. The argument was that if there are to be more city academies, schools will be closed and there’s a cost involved for other schools. They want three city academies in Hackney and one they want is planned for the Kingsland site.”

The new city academies, of which Mossborough is one, are politically sensitive. Wilkinson insists they are not part of a drive towards privatising public services. “I’m very careful about the word privatisation. It’s not what an academy is – it’s state, no fees, no profits, not like private schools.” But pressed on the fundamental difference between city academies and ordinary secondary schools, he said there was “an interest in encouraging enterprise to bring money into schools”.

There will be more school closures to clear the way for city academies. If the chaos surrounding the Kingsland closure is anything to go by, one can only hope the DfES learns from the bumpy ride in Hackney and stops to question the ethos and financial arrangements that are the subtext of these upheavals.

The Learning Trust

Hackney education authority was in serious trouble when it was disbanded in August 2002. It had previously been partly privatised after consultants KPMG told the education secretary that outsourcing was the answer. Nord Anglia took over some key areas of the borough’s education functions. But in October 2000, an Ofsted inspection criticised the council for failure to provide “a secure context for the improvement of educational standards”.

In August 2001, the government announced plans to hand over Hackney’s education provision to an independent, not-for-profit trust. The secretary of state appointed three members to the trust’s board, including the chair and two “independent experts”; a director of education and three members of the senior management team would also be included. Other members would be selected from local heads and governors.

The trust was to be contracted to run education for the borough to “secure maximal revenue and capital funding for Hackney’s schools, including the exploration of a PFI/PPP bid to bring the condition of Hackney’s schools up to standards appropriate to the 21st century”.

Mike Tomlinson, the former chief inspector of schools, became the first chairman of the Learning Trust when he retired from Ofsted in April 2002.

A spokesman says its contract is “managed by the council and they retain ultimate authority for education in the borough. They must approve our annual plan [which] includes our bud get. Councillors sit on our board, and… the education scrutiny panel can review us against any of the terms of the contract. In the memorandum of understanding [annex to the contract] we undertake to respect the role of democratically elected representatives and the council’s scrutiny committees in reviewing decisions and the strategy of the trust.”

Only one member of the board is an elected representative of the local population; the others are selected and therefore largely unaccountable to users. It is this aspect that worries critics of this new semi-privatised LEA, who feel it is undemocratic. Local NUT divisional secretary Mick Regan says: “There is a serious lack of democracy in the Learning Trust, which is in effect a quango.”

Selling Us Off and Selling Us Out?

Posted: June 8, 2003 Filed under: Hackney Council, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Selling Us Off and Selling Us Out?Our Labour council has ignored the wishes of local tenants and residents again

Two weeks ago a “consultation” exercise about the privatisation of estate management on St Mary’s estate ended. At a meeting at Fellows Court community hall, 30 of the 35 people present demanded that tenants be given an “option 3” – a choice to stay with the council. Last week the council’s cabinet voted to press ahead with the transfer of estate management to JSS Pinnacle, a private company.

The IWCA is against privatisation of council services. Not because we have an irrational hatred of the private sector but because the evidence shows it is less efficient, more expensive and less accountable to local people.

Also, if the council wants people to have a choice about their housing, it should mean genuine choice. Options 1 and 2 that tenants & residents were given only involved privatisation, either now or next year. Where was the choice to keep housing management services public? Tenants & residents were refused a ballot on the issue. Instead of allowing us to vote on the matters that affect our lives Labour offers us yet more “consultation”.

All this means is they ask us what we want and if this happens to be different to what they want – they just ignore us. Look at what happened to laburnum school whose fate was decided by so-called consultation with local people. In the face of an overwhelming majority in favour of keeping the school open, a small number of middle-class professionals and Labour councillors voted to press ahead with its closure.

It’s not surprising then that local democracy is at its lowest ebb, and it’s no wonder people are cynical about politicians and voter turn out in elections is so low. And Labour have the nerve to pretend they are worried about it. But the truth is they are responsible for it. The IWCA demands more local democracy, not less. We want people to have a real control over the issues that affect our daily lives.

Over the next few weeks the IWCA has decided to conduct its own ballot on St Mary’s estate to determine how many people would have voted for privatisation given a real choice. We’ll publicise the results. Let us know what you think. The council can’t be allowed walk all over its tenants with such blatant contempt.

Private concerns

Posted: May 9, 2003 Filed under: Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Private concernsArticle from The Guardian Society on estate transfers.

Imagine living on a housing estate where graffiti is cleaned up within 24 hours. That’s just one benefit promised by a pioneering PFI scheme. But is it too good to be true? Terry Macalister reports

Ruth Herrity will be coming full circle when she opens the door of her new home on the Plymouth Grove estate for the first time next week. In 1971, she was one of the first tenants to move on to the Manchester council estate, which was then considered a model of its kind. In 2003, she is one of the first to be rehoused under a fundamental redesign and refurbishment of the estate, now considered long past its best.

But this is no ordinary makeover. The scheme by which Herrity, 78, is swapping her two-bedroom house for a one-bedroom flat represents a new chapter in the history of social housing. For the £99m project is the first application of the controversial private finance initiative (PFI) to existing local authority housing stock.

The move comes at a time when more questions than ever are being raised about the wisdom of the PFI, by which the private sector contracts to renew, run and take the financial risk for public services. Large PFI provider companies, such as Amey, have been brought close to ruin; successive reports have slated the impact of PFI schemes on hospitals; and the chancellor, Gordon Brown, has been accused of using the PFI to cook the Treasury books.

Yet while the political and academic debate rages, dozens of new schemes like Plymouth Grove are quietly moving ahead across the public services. Under the Manchester scheme, a consortium of companies led by the Nationwide Building Society and housebuilder Gleeson will take control of the 1,090-home estate for the next 30 years, demolish some 430 properties and build 600 new ones – many of which will be put up for sale to private buyers.

Because, legally, ownership of the properties is not being transferred, there has been no ballot of council tenants on the estate. However, consultation is said to have taken place over the past four years – a reflection of how long it has taken to get the scheme off the ground.

The companies involved have formed the Grove Village Consortium, put together by the not-for-profit Harvest Housing Group, which will manage the estate on a 30-year contract with Manchester city council. Nationwide is underwriting the physical improvements – including construction of a mile-long “home zone” to slow traffic to walking pace – and a raft of big City helpers, such as accountants PricewaterhouseCoopers and legal firm Eversheds, has been drafted in.

The government is putting up more than £40m for what is the first of eight social housing “pathfinder” PFI projects. But the Labour-run Manchester council is already looking at a second scheme on the Miles Platting estate, where 2,000 properties would be involved. To the ranks of PFI critics, such enthusiasm to hand over public housing to what is known as a “special purpose vehicle” is alarming.

Public services union Unison says Plymouth Grove raises not only organisational concerns but challenges the whole notion of democratic control. And the union fears that the project will be used both to encourage further schemes – one in Islington, north London, is on the way – and to serve as a prototype for the Thames Gateway plans of the deputy prime minister, John Prescott, involving the building of 20,000 new homes.

Unison charges that the government has deliberately left councils with little option but to use PFI by starving them of funds. “Leaving aside issues such as the extra expense of these schemes, we are greatly concerned that local people will no longer have any real control over the houses they live in,” says union spokeswoman Jane Robinson. “Private companies have a primary allegiance to their shareholders – nothing wrong with that – but it’s not appropriate in public services, where there are a range of other responsibilities to be taken into account.”

However, Steve Rumbelow, Manchester council’s director of housing, dismisses these concerns. The issue, he says, is to serve council tenants in the best possible way. “We gave very serious appraisal to PFI and concluded it was the best opportunity to improve not only the housing stock but also the wider environment.”

Design of the new estate by PRP Architects aims to tackle some of the crime, safety and social problems that have plagued it for years. The many rat runs and dark alleyways are being done away with, while the houses are literally being turned round so that they will no longer face inwards, towards each other, but on to the street in a traditional way. The overall effect, it is hoped, will be to integrate with the rest of the city what has become an isolated community.

Rumbelow rejects criticism that some of the properties will be put up for sale – at prices that, according to Gleeson, could reach £120,000 – as he says it is important to change the social mix of the estate if it is to be woven into the fabric of the city. The money from the sale receipts is anyway needed to help regenerate the rest of the housing stock, he says – though no one is prepared to say what profits will be made out of Plymouth Grove, on the grounds that it is commercially sensitive. The nearest is a comment from Ian Perry, chief executive of Harvest, that return on capital is “well under 20% and not much over 10%”.

Gleeson insists it will make nothing in the first 10 years of the project, but is happy to wait. “We are in it for the long haul,” says Dave Whitney, technical manager of Gleeson’s regeneration arm.

Perhaps the biggest supporter of Plymouth Grove is government construction minister Brian Wilson, who argues that the PFI offers the only route to fulfilling the government’s social objectives. “I’m a true believer in PFI and PPP (public-private partnership),” he says. “The complaint that concerns me is not the principle of PFI; it’s the practical difficulties of putting the projects together – what it costs to bid, and how long it takes. Companies can spend millions and still find themselves back at square one.”

That argument holds little water for Unison, which says opposition to the PFI will not go away and believes critics have been emboldened by the latest problems to beset it.

Last month, the board of troubled Amey – once one of the biggest PFI firms – agreed to an £80m takeover offer by Spanish construction group Ferrovial. Amey was until recently a construction and services powerhouse worth £1bn, but it squandered its advantages – contracts to take over parts of London Undergound and various Ministry of Defence and Network Rail deals – through mismanagement and too-fast growth. A black hole was found in the accounts, leading to the exit of two finance directors and, finally, the removal of chief executive Brian Staples.

Similarly, WS Atkins – another key PFI provider – has been put through the financial wringer, ending in the departure of its chief executive, Robin Southwell. The company recently caused shock in Southwark, south London, when it suddenly announced plans to pull out of a £100m contract to manage the borough’s schools. Chairman Michael Jeffries admitted: “We bit off more than we could chew.”

Meanwhile, the torrent of academic papers critical of the PFI has continued. Inveterate critic Allyson Pollock, head of health policy at University College London, has shredded the performance of a PFI scheme for the new Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh. A 24% reduction in numbers of acute beds was supposed to have been offset by efficiency improvements and greater use of care outside the hospital. But these aims have not been met, claim Pollock and co-author Matthew Dunningan, writing in the British Medical Journal, though the hospital trust strongly rejects their findings.

The national audit office – the spending watchdog – has called for more transparency in PFI bond issues, while the Conservatives have accused Brown of being the “Enron chancellor” because he uses the PFI to push spending off his own balance sheet. A recent study by consultancy Capital Economic suggested that £22bn had been moved in this way.

The government insists that all this criticism is just politicking. Wilson claims it is ludicrous to highlight as typical a few PFI deals that have gone wrong. “The reality is that the private sector always did do the main public sector construction contracts, but in the past those firms could walk away if they did a poor job,” the minister says. “The thing about PFI is that it holds those firms to account for the life of a scheme, which can be 30 years.

“I have a hospital in my constituency that took 17 years to build. No one ever crawled all over that contract. It was done by the public sector, and traditionally the public sector just lived with the consequences of late delivery and poor build quality.”

As for the financial troubles of companies such as Amey, Wilson says all contracts have tightly-drawn clauses ensuring that the responsibilities of any failure can be picked up by a range of partners. “There will always be a safety net,” he insists.

The problems encountered by some PFI companies, plus the complexity and costs of bidding for the growing number of contracts, mean British commercial interest could be waning. But the appearance of Ferrovial, through the takeover of Amey, may herald the appearance of many more foreign firms eyeing a slice of Britain’s public services.

Ruth Herrity probably wouldn’t care whether her home and the planned new estate were run from Manchester or Madrid. The important issue for her will be the private sector’s ability to deliver on its promises – which in Plymouth Grove will extend even to erasing all graffiti within 24 hours.

Community in need of rescue

On the corner of Huntsworth Walk sits a colourful children’s play area, decorated with bright orange gates and yellow plaques. One of these depicts a child’s drawing of the ideal home, with large trees in the garden and ducks on the pond.

The stark reality all around is very different. Rows of houses are now boarded up, metal shutters barring all entry. Groups of young men wander aimlessly. Crime is a real problem, as are drugs and guns. “There’s nothing to do,” says a boy, barely in his teens, kicking at a piece of wood. “The only people to talk to are the pigeons.”

Anne O’Malley has been a resident of the Plymouth Grove estate for 30 years. “It began to get bad about eight years ago,” she says. “We were losing good people from the estate. They were moving away and the properties would just be boarded up. The community was haemorrhaging.”

Local residents formed a community group to try to get the estate regenerated, but faced numerous setbacks. “Every time we thought we’d get somewhere, we were knocked back,” says O’Malley. “We seemed to miss out on every pot of money.”

Now, however, there is the PFI. “This is private finance for a social agenda,” says Frances Chaplin, of PRP Architects. “There’s a strong community that has been there since it was built, but the history of the estate has led to its problems.”

Designed according to an American theory of separating cars from people, the estate is a meandering warren of small alleyways and low walls, making it easy for criminals to make their escape.

“This has led to a divorce of property from walkways,” says Chaplin. “We want to achieve a sense of openness. The key to all of this is selective demolition.”

On the estate, the plans have been mostly welcomed. “It’s a good area but it’s just got rundown,” says Liz Lynch, a playworker at the local creche and long-time resident. “We’ve waited a long time for something to be done.”

There has, however, been uncertainty over which homes will be demolished and which refurbished. “Residents have mixed feelings,” says Lynch. “Those losing their homes are upset. Some haven’t been told what phase they are in. My house will be done up, but they’ve said it might be next year or in three years, so I don’t know whether to redecorate.”

A couple of streets away, Pat Daly lives in a neat, terrace house she has spent considerable money doing up. She owns her home, but now finds she is the only one left of her neighbours. “They all moved off, one by one,” she says. “The last one left about nine months ago.”

Daly speaks with feeling about the estate’s sense of community. She says: “My daughter lives on the estate; she’s got kids and I hope she stays. I hope the estate will get better so that when my granddaughters grow up, they can live here as well.”

More on PFI

Recent Comments