Selling Us Off and Selling Us Out?

Posted: June 8, 2003 Filed under: Hackney Council, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Selling Us Off and Selling Us Out?Our Labour council has ignored the wishes of local tenants and residents again

Two weeks ago a “consultation” exercise about the privatisation of estate management on St Mary’s estate ended. At a meeting at Fellows Court community hall, 30 of the 35 people present demanded that tenants be given an “option 3” – a choice to stay with the council. Last week the council’s cabinet voted to press ahead with the transfer of estate management to JSS Pinnacle, a private company.

The IWCA is against privatisation of council services. Not because we have an irrational hatred of the private sector but because the evidence shows it is less efficient, more expensive and less accountable to local people.

Also, if the council wants people to have a choice about their housing, it should mean genuine choice. Options 1 and 2 that tenants & residents were given only involved privatisation, either now or next year. Where was the choice to keep housing management services public? Tenants & residents were refused a ballot on the issue. Instead of allowing us to vote on the matters that affect our lives Labour offers us yet more “consultation”.

All this means is they ask us what we want and if this happens to be different to what they want – they just ignore us. Look at what happened to laburnum school whose fate was decided by so-called consultation with local people. In the face of an overwhelming majority in favour of keeping the school open, a small number of middle-class professionals and Labour councillors voted to press ahead with its closure.

It’s not surprising then that local democracy is at its lowest ebb, and it’s no wonder people are cynical about politicians and voter turn out in elections is so low. And Labour have the nerve to pretend they are worried about it. But the truth is they are responsible for it. The IWCA demands more local democracy, not less. We want people to have a real control over the issues that affect our daily lives.

Over the next few weeks the IWCA has decided to conduct its own ballot on St Mary’s estate to determine how many people would have voted for privatisation given a real choice. We’ll publicise the results. Let us know what you think. The council can’t be allowed walk all over its tenants with such blatant contempt.

Hackney Council is Worst in Country for Benefits Claims

Posted: June 7, 2003 Filed under: Hackney Council Comments Off on Hackney Council is Worst in Country for Benefits ClaimsA report from the Government’s Department of Work and Pensions (as reported in the Hackney Gazette 29th May) shows that Hackney Council is the worst in the country for processing housing benefit claims. The report showed that on average it took the council 142 days to process such a claim.

This comes two years after the council finally sacked the private company ITNet which had caused such misery for so many people. The IWCA was heavily involved in the campaign to get rid of ITNet and ran numerous advice surgeries to help those affected by the delays. We are still getting requests for help from people whose benefits have been delayed and while the situation is better than it was under the benefit bunglers of ITNet, Hackney Council has a duty to improve its service. In a mealy-mouthed response to the Gazette’s report, Cllr Samantha Lloyd claims that things are looking up. Why then is it that neighbouring boroughs with a similar social make-up can expect to get their claims processed so much quicker? And why after sacking ITNet 2 years ago is the Council’s own provision in such a mess?

Independent Kids' Cinema Events

Posted: May 20, 2003 Filed under: Events Comments Off on Independent Kids' Cinema EventsHackney IWCA are putting on two cinema events for young children over half term. The events take place on Thursday 29th May on Goldsmiths and Geffrye estates and are part of the IWCA’s belief that we should try to foster a sense of community that many estates have lost over the years and give young kids something to do and get involved in. The film being shown is Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Entry is 50p and all children get a free drink and bag of crisps as part of the entry fee.

More details:

Goldsmiths Estate Community Centre 11am.

Geffrye Estate Community Centre 3pm.

Open to 5-14 year olds. A teacher or qualified youth worker will be present at each event.

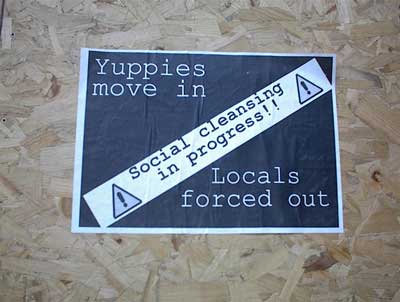

More "Social Cleansing" for Hoxton

Posted: May 16, 2003 Filed under: Gentrification / Regeneration, Shoreditch Comments Off on More "Social Cleansing" for HoxtonThe old cinema on Pitfield Street, Hoxton is next in line to be redeveloped into exclusive flats. It’s part of the process that has been driving local, working class families out of the area and importing new “yuppie settlers”. The IWCA has long opposed this trend in the borough and elsewhere, arguing that the needs of the working class majority should take precedence over those of the moneyed newcomers. But with more and more of our local resources being sold off and buildings such as Laburnum School, Haggerston Pool and many other schools and nurseries under threat, where will it all end?

Below: flyposter making local peoples’ views clear:

"This used to be our library"

Posted: May 16, 2003 Filed under: Community Facilities, Gentrification / Regeneration, Haggerston Comments Off on "This used to be our library"“This used to be our library” – graffiti on a new development off Whiston Rd.

Before becoming a nursery for hospital staff, the new yuppie development was a local library.

Private concerns

Posted: May 9, 2003 Filed under: Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Private concernsArticle from The Guardian Society on estate transfers.

Imagine living on a housing estate where graffiti is cleaned up within 24 hours. That’s just one benefit promised by a pioneering PFI scheme. But is it too good to be true? Terry Macalister reports

Ruth Herrity will be coming full circle when she opens the door of her new home on the Plymouth Grove estate for the first time next week. In 1971, she was one of the first tenants to move on to the Manchester council estate, which was then considered a model of its kind. In 2003, she is one of the first to be rehoused under a fundamental redesign and refurbishment of the estate, now considered long past its best.

But this is no ordinary makeover. The scheme by which Herrity, 78, is swapping her two-bedroom house for a one-bedroom flat represents a new chapter in the history of social housing. For the £99m project is the first application of the controversial private finance initiative (PFI) to existing local authority housing stock.

The move comes at a time when more questions than ever are being raised about the wisdom of the PFI, by which the private sector contracts to renew, run and take the financial risk for public services. Large PFI provider companies, such as Amey, have been brought close to ruin; successive reports have slated the impact of PFI schemes on hospitals; and the chancellor, Gordon Brown, has been accused of using the PFI to cook the Treasury books.

Yet while the political and academic debate rages, dozens of new schemes like Plymouth Grove are quietly moving ahead across the public services. Under the Manchester scheme, a consortium of companies led by the Nationwide Building Society and housebuilder Gleeson will take control of the 1,090-home estate for the next 30 years, demolish some 430 properties and build 600 new ones – many of which will be put up for sale to private buyers.

Because, legally, ownership of the properties is not being transferred, there has been no ballot of council tenants on the estate. However, consultation is said to have taken place over the past four years – a reflection of how long it has taken to get the scheme off the ground.

The companies involved have formed the Grove Village Consortium, put together by the not-for-profit Harvest Housing Group, which will manage the estate on a 30-year contract with Manchester city council. Nationwide is underwriting the physical improvements – including construction of a mile-long “home zone” to slow traffic to walking pace – and a raft of big City helpers, such as accountants PricewaterhouseCoopers and legal firm Eversheds, has been drafted in.

The government is putting up more than £40m for what is the first of eight social housing “pathfinder” PFI projects. But the Labour-run Manchester council is already looking at a second scheme on the Miles Platting estate, where 2,000 properties would be involved. To the ranks of PFI critics, such enthusiasm to hand over public housing to what is known as a “special purpose vehicle” is alarming.

Public services union Unison says Plymouth Grove raises not only organisational concerns but challenges the whole notion of democratic control. And the union fears that the project will be used both to encourage further schemes – one in Islington, north London, is on the way – and to serve as a prototype for the Thames Gateway plans of the deputy prime minister, John Prescott, involving the building of 20,000 new homes.

Unison charges that the government has deliberately left councils with little option but to use PFI by starving them of funds. “Leaving aside issues such as the extra expense of these schemes, we are greatly concerned that local people will no longer have any real control over the houses they live in,” says union spokeswoman Jane Robinson. “Private companies have a primary allegiance to their shareholders – nothing wrong with that – but it’s not appropriate in public services, where there are a range of other responsibilities to be taken into account.”

However, Steve Rumbelow, Manchester council’s director of housing, dismisses these concerns. The issue, he says, is to serve council tenants in the best possible way. “We gave very serious appraisal to PFI and concluded it was the best opportunity to improve not only the housing stock but also the wider environment.”

Design of the new estate by PRP Architects aims to tackle some of the crime, safety and social problems that have plagued it for years. The many rat runs and dark alleyways are being done away with, while the houses are literally being turned round so that they will no longer face inwards, towards each other, but on to the street in a traditional way. The overall effect, it is hoped, will be to integrate with the rest of the city what has become an isolated community.

Rumbelow rejects criticism that some of the properties will be put up for sale – at prices that, according to Gleeson, could reach £120,000 – as he says it is important to change the social mix of the estate if it is to be woven into the fabric of the city. The money from the sale receipts is anyway needed to help regenerate the rest of the housing stock, he says – though no one is prepared to say what profits will be made out of Plymouth Grove, on the grounds that it is commercially sensitive. The nearest is a comment from Ian Perry, chief executive of Harvest, that return on capital is “well under 20% and not much over 10%”.

Gleeson insists it will make nothing in the first 10 years of the project, but is happy to wait. “We are in it for the long haul,” says Dave Whitney, technical manager of Gleeson’s regeneration arm.

Perhaps the biggest supporter of Plymouth Grove is government construction minister Brian Wilson, who argues that the PFI offers the only route to fulfilling the government’s social objectives. “I’m a true believer in PFI and PPP (public-private partnership),” he says. “The complaint that concerns me is not the principle of PFI; it’s the practical difficulties of putting the projects together – what it costs to bid, and how long it takes. Companies can spend millions and still find themselves back at square one.”

That argument holds little water for Unison, which says opposition to the PFI will not go away and believes critics have been emboldened by the latest problems to beset it.

Last month, the board of troubled Amey – once one of the biggest PFI firms – agreed to an £80m takeover offer by Spanish construction group Ferrovial. Amey was until recently a construction and services powerhouse worth £1bn, but it squandered its advantages – contracts to take over parts of London Undergound and various Ministry of Defence and Network Rail deals – through mismanagement and too-fast growth. A black hole was found in the accounts, leading to the exit of two finance directors and, finally, the removal of chief executive Brian Staples.

Similarly, WS Atkins – another key PFI provider – has been put through the financial wringer, ending in the departure of its chief executive, Robin Southwell. The company recently caused shock in Southwark, south London, when it suddenly announced plans to pull out of a £100m contract to manage the borough’s schools. Chairman Michael Jeffries admitted: “We bit off more than we could chew.”

Meanwhile, the torrent of academic papers critical of the PFI has continued. Inveterate critic Allyson Pollock, head of health policy at University College London, has shredded the performance of a PFI scheme for the new Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh. A 24% reduction in numbers of acute beds was supposed to have been offset by efficiency improvements and greater use of care outside the hospital. But these aims have not been met, claim Pollock and co-author Matthew Dunningan, writing in the British Medical Journal, though the hospital trust strongly rejects their findings.

The national audit office – the spending watchdog – has called for more transparency in PFI bond issues, while the Conservatives have accused Brown of being the “Enron chancellor” because he uses the PFI to push spending off his own balance sheet. A recent study by consultancy Capital Economic suggested that £22bn had been moved in this way.

The government insists that all this criticism is just politicking. Wilson claims it is ludicrous to highlight as typical a few PFI deals that have gone wrong. “The reality is that the private sector always did do the main public sector construction contracts, but in the past those firms could walk away if they did a poor job,” the minister says. “The thing about PFI is that it holds those firms to account for the life of a scheme, which can be 30 years.

“I have a hospital in my constituency that took 17 years to build. No one ever crawled all over that contract. It was done by the public sector, and traditionally the public sector just lived with the consequences of late delivery and poor build quality.”

As for the financial troubles of companies such as Amey, Wilson says all contracts have tightly-drawn clauses ensuring that the responsibilities of any failure can be picked up by a range of partners. “There will always be a safety net,” he insists.

The problems encountered by some PFI companies, plus the complexity and costs of bidding for the growing number of contracts, mean British commercial interest could be waning. But the appearance of Ferrovial, through the takeover of Amey, may herald the appearance of many more foreign firms eyeing a slice of Britain’s public services.

Ruth Herrity probably wouldn’t care whether her home and the planned new estate were run from Manchester or Madrid. The important issue for her will be the private sector’s ability to deliver on its promises – which in Plymouth Grove will extend even to erasing all graffiti within 24 hours.

Community in need of rescue

On the corner of Huntsworth Walk sits a colourful children’s play area, decorated with bright orange gates and yellow plaques. One of these depicts a child’s drawing of the ideal home, with large trees in the garden and ducks on the pond.

The stark reality all around is very different. Rows of houses are now boarded up, metal shutters barring all entry. Groups of young men wander aimlessly. Crime is a real problem, as are drugs and guns. “There’s nothing to do,” says a boy, barely in his teens, kicking at a piece of wood. “The only people to talk to are the pigeons.”

Anne O’Malley has been a resident of the Plymouth Grove estate for 30 years. “It began to get bad about eight years ago,” she says. “We were losing good people from the estate. They were moving away and the properties would just be boarded up. The community was haemorrhaging.”

Local residents formed a community group to try to get the estate regenerated, but faced numerous setbacks. “Every time we thought we’d get somewhere, we were knocked back,” says O’Malley. “We seemed to miss out on every pot of money.”

Now, however, there is the PFI. “This is private finance for a social agenda,” says Frances Chaplin, of PRP Architects. “There’s a strong community that has been there since it was built, but the history of the estate has led to its problems.”

Designed according to an American theory of separating cars from people, the estate is a meandering warren of small alleyways and low walls, making it easy for criminals to make their escape.

“This has led to a divorce of property from walkways,” says Chaplin. “We want to achieve a sense of openness. The key to all of this is selective demolition.”

On the estate, the plans have been mostly welcomed. “It’s a good area but it’s just got rundown,” says Liz Lynch, a playworker at the local creche and long-time resident. “We’ve waited a long time for something to be done.”

There has, however, been uncertainty over which homes will be demolished and which refurbished. “Residents have mixed feelings,” says Lynch. “Those losing their homes are upset. Some haven’t been told what phase they are in. My house will be done up, but they’ve said it might be next year or in three years, so I don’t know whether to redecorate.”

A couple of streets away, Pat Daly lives in a neat, terrace house she has spent considerable money doing up. She owns her home, but now finds she is the only one left of her neighbours. “They all moved off, one by one,” she says. “The last one left about nine months ago.”

Daly speaks with feeling about the estate’s sense of community. She says: “My daughter lives on the estate; she’s got kids and I hope she stays. I hope the estate will get better so that when my granddaughters grow up, they can live here as well.”

More on PFI

Marcon Court Campaign Forum

Posted: May 6, 2003 Filed under: Privatisation / Sell Offs, Tenants & Residents Associations Comments Off on Marcon Court Campaign ForumHackney IWCA has opposed transfers of Council housing to private landlords or housing associations on the grounds that – among other things – at least with the Council you know if you don’t like what they’re doing with your housing you can vote to get rid of them. Evidence from all over the country also suggests that rents go up when housing is transferred to profit making landlords and services like estate cleaning and caretaking are the first to be cut to satisfy the demands of business to make money. Marcon Court appears to be another estate the Council are looking to get rid of. Janine Booth, Chair of the TRA explains below and invites people to support the tenants and residents on the estate.

Marcon Court is a Council estate of 81 flats in central Hackney. It has not been refurbished for two decades and is in a poor state of repair.

Hackney Council – after several broken promises to refurbish the estate – is now putting us through a ‘pilot’ process, which will determine whether to refurbish the estate or to transfer it to a new landlord to be demolished and rebuilt.

Our Tenants’ & Residents’ Association wants refurbishment not privatisation. Through bitter experience, we can not be confident that Hackney Council shares our view or has residents’ interests at heart. We suspect that there is an agenda for Marcon Court to be the next in line for the building of costly private housing at the expense of public provision, located as it is near Hackney Downs station – commuter route to the City – and Hackney’s ‘cultural quarter’.

Our TRA is negotiating with the Council on behalf of residents. We know that we will also need a powerful campaign to win for residents, and that this will be most effective if we link up with our allies in the wider community and working-class movement.

So we are holding an open campaign forum, to learn from others’ experiences, to better understand what is happening, to rally support and to generate ideas:

MONDAY 12 MAY 7.30pm

ASPLAND & MARCON COMMUNITY HALL

corner of AMHURST ROAD and MARCON PLACE.

Laburnum School Faces Closure Despite Cash Injection for Hackney

Posted: May 3, 2003 Filed under: Privatisation / Sell Offs, Schools Comments Off on Laburnum School Faces Closure Despite Cash Injection for HackneyAs regulars to this site and readers of the Hackney Independent will know, the IWCA have been heavily involved in the fight to keep Laburnum School open. It now looks as though the school will close but there could be a twist in the tail (which we hope to be able to give you more details about in the very near future).

A vote last month at the Learning Trust, the largely unaccountable organisation which runs Hackney’s schools, was passed to close the school, despite the fact that the school had improved enough to be taken off “special measures”. On top of this, the Hackney Gazette last week revealed that nearly £4 million of new money has been handed to the borough for education which makes you wonder what priorities the council has.

The campaign to keep the school open will go on and we will keep you posted with latest developments as they arise.

Councillors Award Themselves Huge Pay Rises As More Services Slashed

Posted: May 3, 2003 Filed under: Hackney Council Comments Off on Councillors Award Themselves Huge Pay Rises As More Services SlashedHackney councillors have awarded themselves huge pay rises – in many cases between £20,000 and 35,000 – while more local services have faced cutbacks. A spokesperson for the council stated that the increases were agreed back in November but have been paid since January of this year.

Barrie Hibberd, a member of Hackney Tenants and Residents Convention voiced concern over the huge increases in the Hackney Gazette and we’re sure that many others would agree that it’s scandalous to give more money to councillors who have been decimating our services. Recently there have been cutbacks to council gardeners, Laburnum School and Kingsland School face closure and that’s on top of the massive round of cuts from last year which saw funding to a range of community services reduced and in some cases stopped completely.

Clearly these councillors are more interested in getting their noses in the trough than in helping their constituents.

New inquest on police shooting

Posted: April 16, 2003 Filed under: Police Comments Off on New inquest on police shooting

Tuesday April 8, 2003

The Guardian

A father of three, Stanley, 46, was shot twice by specialist firearms officers as he walked home from a pub in Hackney, east London, in September 1999. He was carrying the leg of a coffee table in a tightly-wrapped plastic bag. The two officers have said they thought he was carrying a sawn-off shotgun. The officers also claimed he grasped one end of the table leg into his body and pointed the other at an officer, making it look like a shotgun. Last year’s inquest, however, heard forensic evidence indicating Stanley was facing away from the officers when he was shot in the head and hand.

Deborah Coles, co-director of the pressure group Inquest, said: “We are encouraged by the fact that [the judge] is taking this very seriously. “Obviously the case has big implications for other controversial cases involving the use of state force.”

Recent Comments